Shein vs South African Fashion: How Fast Fashion Is Eroding Our Creative Industry

Shein vs South African Fashion: How Fast Fashion Is Eroding Our Creative Industry

South African fashion stands at a fragile intersection between artistry and algorithm. Once defined by the intimacy of craftsmanship and the individuality of design, it now finds itself contending with a global machine built on speed and imitation. What was once a space for storytelling and cultural reflection is being overtaken by an industry that thrives on disposability. At the centre of this disruption sits Shein, a retail phenomenon that has transformed how the world consumes clothing and in doing so, threatens to erase the very essence of what makes South African fashion distinct.

Shein’s rise represents one of the most significant shifts in consumer culture in recent history. What began as a fringe online retailer has evolved into a behemoth that dominates the global fashion economy through speed, affordability and algorithmic precision. Its model is deceptively simple: identify micro-trends, manufacture them instantly and distribute them globally at prices that seem almost absurd. The effect is immediate. Consumers feel as though they are buying into the pulse of global style in real time. But behind this illusion of accessibility lies a system that is quietly dismantling the very foundations of fashion economies around the world, including South Africa’s.

South Africa’s fashion industry has never existed in isolation. It is intertwined with the textile sector, small-scale manufacturing, design education, retail distribution and the livelihoods of countless artisans. Every local garment produced supports a network of people who contribute to its journey. Shein bypasses all of that. Its presence in the South African market is not just competition; it is disruption on a scale that feels almost existential. The platform has conditioned a generation of consumers to believe that a new outfit should cost less than a meal, that style is disposable and that the value of fashion lies not in quality or craftsmanship but in instant gratification.

It is difficult to compete with an entity that plays by no conventional rules. Shein’s production model operates beyond national borders, beyond ethical accountability and beyond the pace of traditional design cycles. Thousands of new styles are uploaded daily, feeding an algorithm that reads social media engagement as data, not culture. What emerges is an infinite feedback loop of consumption, desire and obsolescence. By the time a South African designer finalises a collection that honours local craftsmanship, Shein has already flooded the market with replicas inspired by global street style, independent designers’ work and trending aesthetics from abroad.

The cost of this goes far beyond the economic. It is cultural. South African fashion has always been about storytelling, about tracing our identity through texture, silhouette and detail. Designers like Thebe Magugu, Rich Mnisi and Laduma Ngxokolo have shown the world that South African design is not a subgenre of global fashion but a vanguard of its future. Their work carries emotional weight because it is born of a context. When that narrative is drowned out by an influx of cheap imports, what is lost is not merely a market share but a sense of meaning.

Fast fashion’s impact is often discussed in environmental terms and rightly so. The waste generated by mass production, the reliance on synthetic fabrics and the carbon footprint of global logistics are staggering. But in South Africa, the damage manifests in another way. It manifests in empty storefronts of local boutiques that cannot compete with prices driven by scale and exploitation. It manifests in the quiet disillusionment of young designers who realise that their craft, no matter how inspired, cannot survive a market addicted to immediacy. It manifests in the gradual erosion of a cultural ecosystem that once prized originality, texture and soul.

MaXhosa Africa

Driven by algorithms that reward novelty, the fashion environment has become one where clothing is worn once, photographed and discarded. It is not selling garments; it is selling content. The garment becomes a prop, a temporary costume in the pursuit of engagement metrics. What disappears in this process is the emotional relationship between person and clothing, the sense of identity that comes from choosing something because it speaks to who you are rather than what is trending this week.

For South Africa, the stakes are particularly high. Our local fashion industry is not just an aesthetic enterprise; it is an economic one. It provides employment in a country where unemployment remains among the highest in the world. Every locally made piece sustains families, communities and small businesses. When those purchases shift toward global online retailers who do not contribute to local tax systems, wages or infrastructure, we lose more than economic output. We lose agency over our own creative economy.

Thebe Magugu

The urgency of addressing Shein’s influence became even clearer in October 2025, when Minister of Sport, Arts and Culture Gayton McKenzie met with representatives of the global fashion brand on the margins of South Africa Focus Week in Singapore. The meeting was framed around potential collaborations between Shein and South Africa’s creative, fashion and sports sectors, with an emphasis on inclusive sporting initiatives and opportunities for young South African designers and athletes.

The meeting exposes a profound misalignment of priorities within South Africa’s leadership. By publicly aligning with Shein, a multinational whose business model systematically undercuts local designers and erodes the creative ecosystem, Minister McKenzie risks legitimising the very forces threatening the survival of South African fashion. Rather than defending local industry or setting clear conditions to protect homegrown talent, the engagement appears to normalise fast fashion’s dominance, sending a signal that international corporate influence can supersede the needs of South African creators. It is a troubling example of policy optics taking precedence over substantive support for the designers and artisans who sustain the industry and it undermines any claims of genuine commitment to empowering local talent.

MaXhosa Africa

This moment is made more urgent by the recent announcement that South African Fashion Week is taking a strategic pause. The pause, intended to reassess the industry’s direction, highlights the fragility of local platforms in a market increasingly dominated by global players with deep pockets and unregulated supply chains. While local initiatives pause to reflect and strategise, a foreign brand is courting official endorsement and visibility, reinforcing the imbalance between local craftsmanship and global corporate influence.

There is a growing sense among South African designers that they are shouting into a void. They are producing collections that celebrate South African modernity, sustainability and craftsmanship, but they are doing so in a marketplace that has been conditioned to undervalue those very qualities. Consumers want to support local, but not at local prices. The irony is that the same audiences who celebrate South African excellence on runways and in media are also the ones clicking “add to cart” on Shein hauls. It is a dissonance that reflects a broader crisis of consciousness, a detachment between what we say we value and what we actually choose.

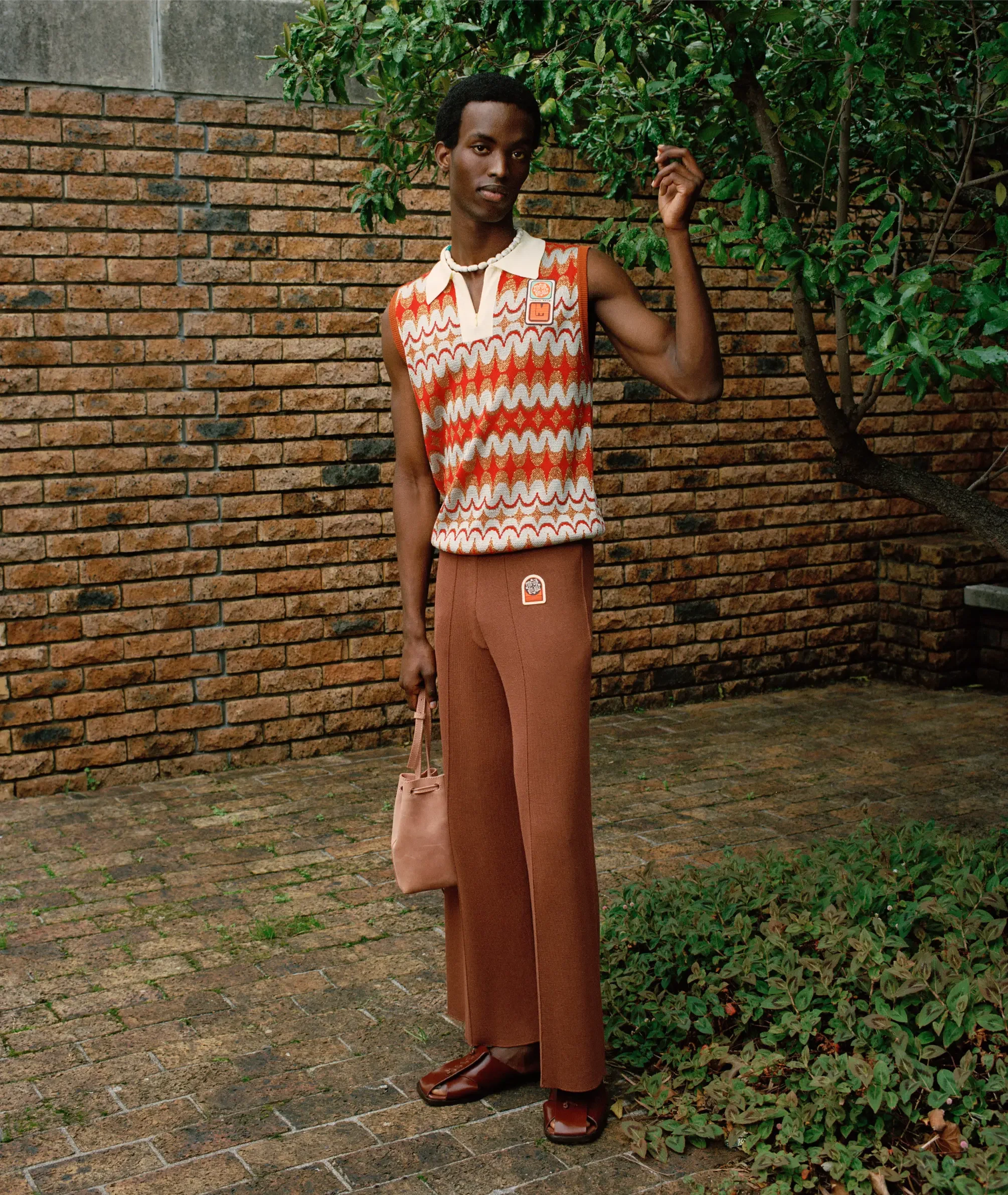

Lukhanyo Mdingi

To critique Shein is not to condemn accessibility. Fashion should be democratic. The problem is not that people want affordable clothing; it is that affordability has been achieved through a system that externalises its true costs. When garments are produced in factories where workers earn less than a living wage, when quality is sacrificed for quantity, when waste becomes inevitable because the product was never designed to last, we are not buying cheap fashion; we are subsidising exploitation.

There is an urgent need for cultural re-education, a reintroduction to what fashion is supposed to mean. South African consumers need to understand that when we purchase a locally made item, we are investing in something that holds value beyond price. We are sustaining an ecosystem that includes designers, patternmakers, seamstresses, textile suppliers, photographers and stylists. We are voting for creativity, for craftsmanship and for the continuation of a uniquely South African narrative in global fashion.

Supporting local fashion has to move beyond admiration and into action. Visibility alone is no longer enough. Real change begins when consumers make deliberate choices that sustain the industry. That means buying from local designers, renting instead of hoarding, recycling responsibly and demanding transparency from every brand we support.

Ultimately, the Shein phenomenon exposes something uncomfortable about the global fashion psyche. It reveals how easily cultural value can be replaced by commercial velocity, how the pursuit of newness has replaced the appreciation of craft. In South Africa, this is not just an abstract debate about globalisation; it is a direct threat to an industry that carries the soul of our creativity.

IMPRINT ZA